The Black Berets in the Brown Waters of Vietnam: The U.S Navy Riverine Patrol Operations.

Based on the interview of Don Knorr, Voice Communications operator in the Vietnam War 1968 - 1971

Don in his Black Beret.

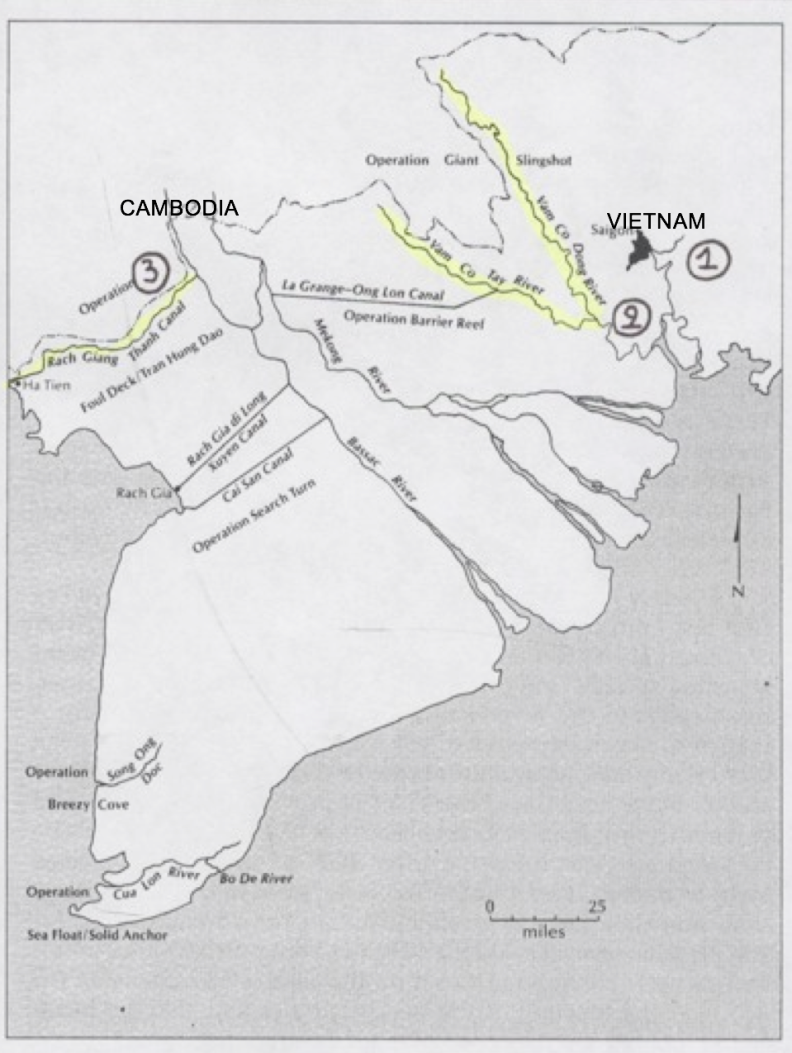

Don Knorr was born January 27, 1949 in Marshville, Wisconsin, USA. Right after he graduated from high school, he volunteered in the US Navy, thinking it would keep him from ending up on the ground in Vietnam, as several other sailors did when they received their draft notices for the Army. This led him to join the Vietnam war from 1968 to 1971, where he worked in voice communications as a radio operator. He served three tours in Vietnam, each of 12 months, and each time he went back, he was assigned some place else. His first assignment from 1968 to 1969 was to escort ships and patrol the South China Sea around Na Bay. His second assignment from 1969 to 1970 was in Ben Ouc, where he patrolled up and down the two rivers Vam Co Dong and Vam Co Tay, located around the Parrot’s Beak: a part of Cambodia coming into Vietnam. His mission there was to prevent the enemy’s infiltration of manpower, foodstuffs, medical supplies, arms, and ammunition into South Vietnam. For his third year (1970-1971) he was assigned to Patrol Boat River operations (PBR’s) where he patrolled a canal that runs along the Western side of Vietnam right below the Cambodian border. Mr. Don Knorr gained extensive experience in riverine patrol operations, which is a fascinating and somewhat overlooked aspect of the war. In this paper, I analyze the purpose of the riverine patrols in the brown waters of Vietnam through the example of Mr Knorr who coordinated these operations through voice communications. This study of riverine patrol operations can help us learn about how American military strategies evolved over the course of the Vietnam War. In order to determine the purpose of the riverine patrols operations, I will first discuss the reason for the US Navy riverine operations in Vietnam. Then I will describe the missions of the Patrol Boat River operations. Finally, I will argue that despite the fact that the US Navy had no formal riverine strategy before entering the Vietnam War those riverine patrols operations were successful in most of their intended missions and contributed to the establishment of a riverine warfare doctrine.

During the interview, Don Knorr declared that everybody in the Navy firmly believed that if you control the rivers of Vietnam you control the whole country. In fact, throughout Vietnam’s history, inland waterways have been vital to the country’s growth and development because they represent arteries of transportation, commerce and communication. The canals and rivers crossing the country, have therefore been key military areas in times of conflict and particularly in the Vietnam War.[1] Many scholars agree that the nature of the geography and demographics in Vietnam ultimately made control of the rivers and coastal regions vital[2]. The Bucklew Report of 1964 emphasized the crucial importance of rivers in Vietnam and influenced the establishment of an American naval presence in the Mekong Delta. In January 1964, Captain Philip H. Buclew with 8 naval officers went to Vietnam as part of the “Vietnam Delta Infiltration Study Group” to determine the extent of Communist movement in the Mekong Delta. The report showed that the enemy forces used South Vietnam’s waterways to transport foodstuffs, medical supplies, infiltrate weapons, equipment, and men[3]. Because the waterways were vital to the enemy, it was inevitable that a significant phase of the counterinsurgency war in Vietnam would be fought on water[4]. To counter this flow of material, men and ammunitions, the study recommended that a river force, including both river patrol boats and a landing force, be created[5]. Besides, Naval and military leaders also considered history before deploying a riverine force onto South Vietnamese rivers. William Fulton in Riverine Operations 1966-1969 contends that there was “a tradition of past American success in riverine operations”. All of these documents contributed to the decision of the Secretary of Defense in August 1965 to authorize the navy to wage riverine warfare in Vietnam. On the 18th of December 1965 the River Patrol Force was created under the code name Operation Game Warden[6]. This new force was designated Task Force 116, and Don Knorr later become part of this force.

Don Knorr explained that the missions of the River Patrol Force were broad but could be summarized to four missions.

First, the river boats’ principal mission consisted of monitoring the rivers, stopping and checking people as they come and make sure that they were not carrying weapons. It was his mission during his second tour in Vietnam from 1969 to 1970, which was the worst one according to him. They basically assumed the role of “police” in the Vietnam’s rivers. He recalls that in these perilous rivers and canals it was difficult to say who was your friend and who was your enemy so they had to stop and search the vessels.

Don knorr pointed out that it was even harder to distinguish your enemy from your friends in the darkness and that constituted another mission of the patrol river force: they had to intercept boats at night. Most often the attacks occurred at night, Don confessed that during the day nothing really happened. He explained that you could do either night or day patrolling, but you always alternated. It fluctuated because of staff limitation and the working hours were either 8 hours on and 8 hours off the boat or 12 on and 12 off.

Don Knorr told me that another mission was to transport and infiltrate Navy Seals to a point and then come back to pick them up.

The last mission was to escort ships and protect them from the enemy. Don was assigned this task during his first tour in Vietnam from 1968 to 1969, when he escorted ships from the rivers in Na Bay to the South China sea and vice versa. His own mission in all of these operations was to request backup if a boat was shot, he would immediately call artillery from the Navy and air support. Though, he indicated that the boats always patrolled in pairs permitting one to cover the other during searches or other investigations and making enemy ambushes less likely to happen[7].

Besides, Don mentioned that each riverine patrol boat (PBR) consisted of a 5 man crew with one person in the front who took care of the two large machine guns. In the driving compartment there were the captain and his assistant. Behind them, one person used another machine gun. Then the last sailor was on board with a smaller caliber (M16) and could go either side of the boat.

Even if the PBR have machine guns at their disposal, Cutler explained that they were usually not heavily armed-equipped in order to be lighter and faster[8]. Don notified that the PBR’ speed allowed it to be partially protected from shootings, benefitting from extreme maneuverability. Yet Don considers himself very lucky because his role in the army put him in a relatively “safe spot” where his life was not in direct danger at all time compared to the men on the ground. Indeed for his last tour, as an advisor from 1970 to 1971, he never saw a firefight in the canal.

However his job was not without risk, as Don’s most turbulent memory was during his second tour from 1969 to 1970, where he participated in the Operation Giant Slingshot. This operation took place on the Vam Co Tay and Vam Co Dong rivers which converged on the Parrot’s Beak: a part of “neutral” Cambodia that jutted into Vietnam. The goal of this operation was to stop the flow of arms and supplies of the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces that came all the way from the north, down on the Ho Chi Minh Trail and destined to resupply infiltrated the troops in the south[9]. According to Kirshen, a boat captain who participated in the operation Giant Slingshot, it was a hotly contested area and he witnessed to several shootings. In 1969, a large number of PBRs departed their bases on the Vam Co Dong and established control along the river, as described by Don Knorr during the interview[10]. The Giant Slingshot Operation was a success. Between the 8th of February and the 4th of April, the PBR unit killed more than a hundred enemies while suffering the loss of only two PBRs and four sailors. Besides, a document found on a dead Communist confirmed the effectiveness of the Giant Slingshot operations. The writer complained that the operation “had resulted in heavy loses inflicted on our forces”[11].

Don Knorr, himself believed that the riverine patrol boat operations were successful and beneficial to the overall conduct of the war. The patrol operations certainly succeeded in controlling the traffic of the enemy in the rivers of Vietnam. Yet, we should not draw hasty conclusions, because as Cutler argues, it is difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of the riverine operations for several reasons.

First, it is suspect to claim the success of any component of a lost war, because the ultimate loss of the war makes it doubtful[12].

Furthermore, the activity of infiltration is clandestine and the captures are the only known data while the misses remain unknown. Thus, it is possible that boats passed without the awareness of US intelligence. Besides, without complete testimony from the enemy, it is not possible to assess accurately the effectiveness of the riverine patrol operations. Yet stories of Viet Cong soldiers prove that the PBR had prevented them from moving supplies on the river. One even reported he had been without food for two or three days[13].

Many contemporary analyst join Don Knorr’s affirmation that the Riverine Patrol Operations fulfilled successfully their objectives. It was for sure a significant factor in reducing the enemy’s free use of river lines of communication. As a matter of fact, the North Enemies were forced to change their tactics and moved supplies through the jungle, which was much more complicated than using the rivers. Don Knorr participated directly to the success of the riverine operations by communication with other PBR or calling air support. Indeed, close air support and ground force communication was also essential to the success of riverine forces. The increase of U.S. presence in the delta, especially after 1968, enabled them to infiltrate significant combat forces for the invasion of Cambodia in 1970 and to counter the Communist Easter Offensive north of Saigon in 1972. Besides, the Mekong Delta was one of the last areas to fall into enemy hands in 1975[14]. Cutler explained that the PBR could have been a disaster, because it was tested in an atmosphere of urgency and without doctrine. Instead, Cutler stated that the PBR operation proved to be “a fierce little combatant” that accomplished its mission[15]. According to him, the men who served on the PBRs were the most important factor in the boat’s success. He changed the official meaning of the letters PBR to Proud - Brave and Reliable to characterize the PBR sailors.

More importantly, the river patrol operations added to US knowledge of riverine operations. In fact, despite the Navy’s long history of river operations, in 1965 there were no codified doctrine or manuals on river patrol operations. Initially, the brown water navy centered its tactics on a “body of theory or a collection of ideas based on experience and common sense”. That means that, the first sailors to be deployed in Vietnam conducted their operations only on informal doctrine (reports, verbal orders…)[16]. This lack of formal strategy meant that flexibility was inherent in the river force[17]. With little modern river warfare experience and no doctrine of its own to follow, the U.S. Navy proved adept at organizing, equipping, training, deploying, and supplying combat-ready forces. Based on operational experience and rules of engagement (ROE), the river patrol units developed their own operating procedures and tactics. In fact Don Knorr learned these newly created operation orders in his training in 1968. He remembered from these rules, that you should be careful of what you said on the radio, should not swear and use codes because they were monitored by the enemy. In essence, the century and a half of riverine combat experience culminated in formal publications that produced well-trained and prepared brown water sailors[18]. In 1971, the Navy created the Riverine Warfare Manual which presents concepts and techniques as a guide for riverine warfare. This experience and expertise gained by America’s river warfare forces continues to enlighten more recent military operations by creating a formalized tactical doctrine[19]. In fact, these methods contributed to the success of riverine patrol operations in Iraq, while patrolling the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers[20].

In conclusion, it can be said that Don Knorr offers relevant insights on the Riverine Patrol Operations in the brown waters of Vietnam. His firsthand insight into the Vietnam war helped me understand the purpose of riverine patrols in the brown waters of Vietnam. By the end of the war, the Vietnam Navy had become a combat-hardened force that fought and won many battles and partly secured the country’s inland waterways. Even though the Viet Cong showed an extraordinary ability to adapt their strategy in moving supplies along the Cambodian border into South Vietnam, the riverine patrol operations still managed to considerably reduce enemy movement. In fact, they inflicted real damage on the Viet Cong’s freedom of movement and largely succeeded in most of their intended missions. In the end, the Vietnam War marked a turning point in the emergence of a formalized riverine warfare tactical doctrine for the U.S. Navy. It materialized by the creation of the Riverine Warfare Manual in 1971, in which concepts and techniques are explained to guide officers in the riverine warfare operations.

Réalisé par Léa Berthon, étudiante Master 2, promotion 2018-2019

- 1968-1969: Don’s First Tour

- 1969-1970: Don’s Second Tour

- 1970-1971: Don’s Third Tour

REFERENCES:

Interviews with Don Knorr, voice communications operator in the US Navy, 1968-1971, Vietnam. February, 17, 2017 / March, 2017.

Kirshen, Richard H. Vietnam War River Patrol: A U.S. Gunboat Captain Returns to the Mekong Delta. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2017.

Herring, John. America’s Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950-1975. Third Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996.

Marolda, Edward J. and Dunnavent, R. Blake. Combat at Close Quarters: Warfare on the Rivers and Canals of Vietnam. Washington, D.C: Naval History & Heritage Command, 2015.

Cutler, Thomas J. Brown Water, Black Berets: Coastal and Riverine Warfare in Vietnam. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1988.

Fulton, William B. Vietnam Studies: Riverine Operations 1966-1969. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, 1973.

Bassett, William B. The Birth of Modern Riverine Warfare: U.S. Riverine Operations in the Vietnam War. Joint Military Operations Department. Newport, RI: Naval War College, 2006.

Dunnavent, R. Blake. Brown Water Warfare: The U.S. Navy in Riverine Warfare and the Emergence of a Tactical Doctrine, 1775–1970. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003.

CITATIONS:

[1] Blake R. Dunnavent, Brown Water Warfare: The U.S. Navy in Riverine Warfare and the Emergence of a Tactical Doctrine, 1775–1970 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003), XVII

[2] William Bassett, The Birth of Modern Riverine Warfare: U.S. Riverine Operations in the Vietnam War (Newport, RI: Naval War College, 2006), 3

[3] Edward J. Marolda and Blake R. Dunnavent, Combat at Close Quarters: Warfare on the Rivers and Canals of Vietnam (Washington, D.C: Naval History & Heritage Command 2015), 17.

[4] William B. Bassett, The Birth of Modern Riverine Warfare: U.S. Riverine Operations in the Vietnam War (Newport, RI: Naval War College, 2006), 7.

[5] Blake R. Dunnavent, Brown Water Warfare: The U.S. Navy in Riverine Warfare and the Emergence of a Tactical Doctrine, 1775–1970 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003), 111

[6] Thomas J. Cutler, Brown Water, Black Berets: Coastal and Riverine Warfare in Vietnam,(Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1988), 159. 6.

[7] Thomas J. Cutler, Brown Water, Black Berets: Coastal and Riverine Warfare in Vietnam, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1988), 156

[8] Ibid. p.157

[9] Richard H. Kirshen, Vietnam War River Patrol: A U.S. Gunboat Captain Returns to the Mekong Delta, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2017), 79.

[10] Blake R. Dunnavent, Brown Water Warfare: The U.S. Navy in Riverine Warfare and the Emergence of a Tactical Doctrine, 1775–1970 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003), 124-125.

[11] Edward J. Marolda and Blake R. Dunnavent, Combat at Close Quarters: Warfare on the Rivers and Canals of Vietnam (Washington, D.C: Naval History & Heritage Command 2015), 53.

[12] Thomas J. Cutler, Brown Water, Black Berets: Coastal and Riverine Warfare in Vietnam, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1988), 133.

[13] Ibid. 205

[14] Edward J. Marolda and Blake R. Dunnavent, Combat at Close Quarters: Warfare on the Rivers and Canals of Vietnam (Washington, D.C: Naval History & Heritage Command 2015), 79.

[15] Thomas J. Cutler, Brown Water, Black Berets: Coastal and Riverine Warfare in Vietnam, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1988), 158.

[16] Blake R. Dunnavent, Brown Water Warfare: The U.S. Navy in Riverine Warfare and the Emergence of a Tactical Doctrine, 1775–1970 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003), 129.

[17] Thomas J. Cutler, Brown Water, Black Berets: Coastal and Riverine Warfare in Vietnam, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1988), 161.

[18] Blake R. Dunnavent, Brown Water Warfare: The U.S. Navy in Riverine Warfare and the Emergence of a Tactical Doctrine, 1775–1970 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003), 132.

[19] Edward J. Marolda and Blake R. Dunnavent, Combat at Close Quarters: Warfare on the Rivers and Canals of Vietnam (Washington, D.C: Naval History & Heritage Command 2015), 79.

[20] “Riverine Fact Sheet,” www. necc.navy.mil, 1-2.

1 commentaire